By Daniel Frank, Director, Virginia Tech Pesticide Programs

[This article was originally published in VTPP Quarterly: A Newsletter from Virginia Tech Pesticide Programs. It is used here with permission from the author. We try to, at least once a year, share research-based information about ticks and tick-borne diseases with VMN volunteers, because ticks are likely one of the most common safety hazards that our volunteers encounter during their training and service activities. Please help keep yourself and members of the public who attend your programs safe by reminding them of the recommended personal protection measures they can take.--M. Prysby]

[This article was originally published in VTPP Quarterly: A Newsletter from Virginia Tech Pesticide Programs. It is used here with permission from the author. We try to, at least once a year, share research-based information about ticks and tick-borne diseases with VMN volunteers, because ticks are likely one of the most common safety hazards that our volunteers encounter during their training and service activities. Please help keep yourself and members of the public who attend your programs safe by reminding them of the recommended personal protection measures they can take.--M. Prysby]

Deer tick, Ixodes scapularis. Photo by Erik Karits on Unsplash

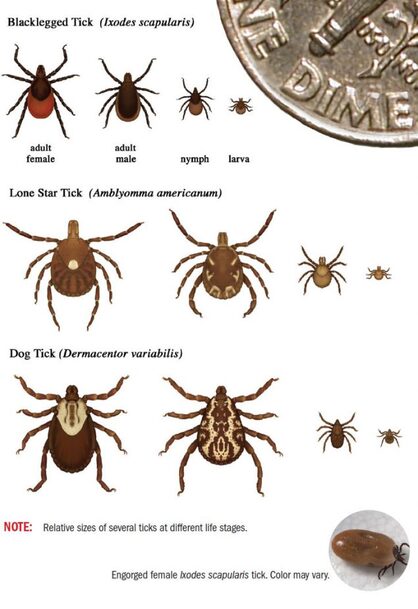

Ticks that commonly bite humans. Image from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Ticks that commonly bite humans. Image from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. With the advent of spring and warming weather, more people are venturing outdoors to work and play. This also means it is a good time to start getting in the habit of protecting yourself from ticks. Ticks (Family: Ixodidae) are a parasitic group of arthropods that feed on blood from their animal hosts. They are active year-round (even in the winter when temperatures are above freezing), and are considered important medical/veterinary pests because of their ability to transmit a number of disease agents.

Life History and Habits

The lifecycle of ticks consists of four stages; the egg, six-legged larva (often called seed ticks), eight-legged nymph, and adult (also with eight legs). Ticks must feed (take a blood meal) at each stage to complete their lifecycle, which can take one to three years to complete. Each stage generally feeds on a different animal host. Ticks become engorged after taking a blood meal and drop from the host to find a protected location to molt to the next stage. Adult females begin laying eggs shortly after their final blood meal. Under favorable conditions, ticks can survive for several months without feeding.

Ticks do not jump or drop from trees onto their hosts. They wait in a position known as “questing.” Questing ticks will rest on vegetation (often at ground level to about waist height) with their front legs outstretched waiting to climb on a suitable host as it brushes by. Various stimuli such as body heat, the carbon dioxide that animals produce when they exhale, movement, and other bodily cues of the host can intensify questing

behavior. Some ticks may quickly attach and begin feeding once on a host. Others may wander for up to a few hours before settling on a spot to feed.

In order for a tick to take a blood meal without being detected or dislodged, it injects small amounts of saliva with anesthetic properties at the site of attachment. If the tick is infected with a pathogen, it is transmitted to the host through the saliva. A tick initially acquires the pathogen when feeding on an infected host.

Common Species and Medical Importance

Common tick species affecting humans in Virginia include the American dog tick (Dermacentor variabilis), blacklegged or deer tick (Ixodes scapularis), and lone star tick (Amblyomma americanum) (see image).

The American dog tick is commonly encountered west of the Blue Ridge Mountains in Virginia. Although it can be found feeding on dogs (as the name suggests), it will readily feed on numerous other animal hosts including humans. American dog ticks are the primary carrier for the pathogen causing Rocky Mountain spotted fever. It can also transmit the pathogen responsible for tularemia.

The blacklegged or deer tick is commonly encountered in mixed forests and along woodland edges throughout Virginia. The larval and nymphal stages typically feed on small rodents (the preferred host is the white-footed mouse). Deer are the primary hosts during the adult stage. Blacklegged ticks are the primary carrier for the pathogen causing Lyme disease. They also transmit anaplasmosis, babesiosis, and Powassan virus.

The lone star tick is commonly encountered in the Piedmont and Coastal Plain regions of Virginia. Lone star ticks transmit the pathogens causing ehrlichiosis, Rocky Mountain spotted fever, southern tick-associated rash illness (STARI), and tularemia.

Tick Integrated Pest Management

Personal Protection

The most important and effective way to protect yourself from ticks and tick-borne diseases is to regularly check your entire body for attached ticks, and promptly remove and kill any ticks found. The probability of a tick transmitting a disease-causing pathogen increases the longer an infected tick is attached. For example, in the case of Lyme disease, the tick must be attached for at least 36 to 48 hours to transmit the disease. Ticks may feed anywhere on the body, but can commonly be found around the scalp, behind the ears, under armpits or behind knees, and around waistbands. Because tick bites are often painless, most people will be unaware that they have an attached tick without careful visual inspection.

When entering habitat with a high risk of tick exposure (i.e., heavy woods, tall grasses, woodland edges), there are several precautions you can take to limit contact with ticks. When hiking along trails, stay in the center and avoid brushing against weeds and tall grass. Wear light-colored clothing with long pants tucked into socks and shirts tucked into pants. This can make ticks easier to spot and keep them on the outside of clothes. Using a tick repellent on skin and clothing is also highly recommended. The Environmental Protection Agency and Centers for Disease Control list DEET, picaridin, IR3535, oil of lemon eucalyptus, and 2-undecanone as effective active ingredients in tick repellents. Wearing permethrin treated clothing is also particularly effective. If treating clothing yourself, be sure to follow all label instructions and allow the product to dry completely before wearing.

If an attached tick is found, remove it using thin tipped tweezers or forceps. Grasp the tick as close to the skin as possible, and pull the tick upward with steady even pressure. The idea is to remove the tick with its

mouthparts intact to reduce the risk of infection. Other methods of tick removal (i.e., petroleum jelly, heat from matches) are not recommended. Removed ticks can be stored in rubbing alcohol in case disease symptoms develop and the tick needs to be identified. National laboratories can also provide Lyme and other tick-borne disease testing on removed ticks (fees usually range between $50-$100).

Landscape Management

Desiccation (drying out) is a major cause of natural tick mortality. Taking steps to reduce surface humidity and moisture can make an area less favorable for ticks. For example, keeping grass and weeds mowed, clearing leaf litter, and pruning/removing trees to increase sunlight in areas frequently used by people can help discourage ticks.

There is a positive correlation between the abundance and distribution of the blacklegged tick and the size of white-tailed deer populations. Adult blacklegged ticks preferentially feed on deer. Therefore, deer may bring engorged adult female ticks into a landscape where they can lay eggs and increase tick numbers. Deer management options such as fencing, repellents, guard animals, and deer resistant landscape plantings can help reduce tick populations in an area.

Chemical Controls

If landscape management practices fail to provide adequate tick control, insecticides (called “acaricides” when used for ticks) can help reduce populations. Appropriately labeled acaricides should be applied only to areas where ticks may inhabit (e.g., woodland edges, shady perennial beds). It is seldom necessary to treat an entire yard or lawn area because ticks are unlikely to inhabit areas exposed to full sunlight. Common active ingredients used by pest control professionals include those in the pyrethroid class of insecticides (e.g., bifenthrin [Talstar P, Up-Star]; cyfluthrin [Tempo], pyrethrins [ExciteR, Pyganic]). Spray treatments are most effective when applied using a high-pressure sprayer in the early spring. An additional application in the fall can be used to target adult ticks if populations are particularly high. Pyrethroids should not be applied when

pollinators are active, near areas where plants are blooming, or near standing water, streams, or rivers to reduce negative effects to the environment and non-target organisms.

Another option to treat ticks around the home is to target acaracides on small mammals that may be living in the area. In many instances, mice are the reservoir hosts responsible for producing disease carrying ticks (particularly Lyme disease). Rodent targeted devices such as “tick tubes” (e.g., Thermacell), are cardboard tubes containing cotton balls treated with an acaricide. The idea is to spread these around the landscape where mice, or other rodents, will find them and take the cotton as nesting material. Then, any larval or nymphal ticks attached to the animal will contact the acaricide on its fur and die.

Life History and Habits

The lifecycle of ticks consists of four stages; the egg, six-legged larva (often called seed ticks), eight-legged nymph, and adult (also with eight legs). Ticks must feed (take a blood meal) at each stage to complete their lifecycle, which can take one to three years to complete. Each stage generally feeds on a different animal host. Ticks become engorged after taking a blood meal and drop from the host to find a protected location to molt to the next stage. Adult females begin laying eggs shortly after their final blood meal. Under favorable conditions, ticks can survive for several months without feeding.

Ticks do not jump or drop from trees onto their hosts. They wait in a position known as “questing.” Questing ticks will rest on vegetation (often at ground level to about waist height) with their front legs outstretched waiting to climb on a suitable host as it brushes by. Various stimuli such as body heat, the carbon dioxide that animals produce when they exhale, movement, and other bodily cues of the host can intensify questing

behavior. Some ticks may quickly attach and begin feeding once on a host. Others may wander for up to a few hours before settling on a spot to feed.

In order for a tick to take a blood meal without being detected or dislodged, it injects small amounts of saliva with anesthetic properties at the site of attachment. If the tick is infected with a pathogen, it is transmitted to the host through the saliva. A tick initially acquires the pathogen when feeding on an infected host.

Common Species and Medical Importance

Common tick species affecting humans in Virginia include the American dog tick (Dermacentor variabilis), blacklegged or deer tick (Ixodes scapularis), and lone star tick (Amblyomma americanum) (see image).

The American dog tick is commonly encountered west of the Blue Ridge Mountains in Virginia. Although it can be found feeding on dogs (as the name suggests), it will readily feed on numerous other animal hosts including humans. American dog ticks are the primary carrier for the pathogen causing Rocky Mountain spotted fever. It can also transmit the pathogen responsible for tularemia.

The blacklegged or deer tick is commonly encountered in mixed forests and along woodland edges throughout Virginia. The larval and nymphal stages typically feed on small rodents (the preferred host is the white-footed mouse). Deer are the primary hosts during the adult stage. Blacklegged ticks are the primary carrier for the pathogen causing Lyme disease. They also transmit anaplasmosis, babesiosis, and Powassan virus.

The lone star tick is commonly encountered in the Piedmont and Coastal Plain regions of Virginia. Lone star ticks transmit the pathogens causing ehrlichiosis, Rocky Mountain spotted fever, southern tick-associated rash illness (STARI), and tularemia.

Tick Integrated Pest Management

Personal Protection

The most important and effective way to protect yourself from ticks and tick-borne diseases is to regularly check your entire body for attached ticks, and promptly remove and kill any ticks found. The probability of a tick transmitting a disease-causing pathogen increases the longer an infected tick is attached. For example, in the case of Lyme disease, the tick must be attached for at least 36 to 48 hours to transmit the disease. Ticks may feed anywhere on the body, but can commonly be found around the scalp, behind the ears, under armpits or behind knees, and around waistbands. Because tick bites are often painless, most people will be unaware that they have an attached tick without careful visual inspection.

When entering habitat with a high risk of tick exposure (i.e., heavy woods, tall grasses, woodland edges), there are several precautions you can take to limit contact with ticks. When hiking along trails, stay in the center and avoid brushing against weeds and tall grass. Wear light-colored clothing with long pants tucked into socks and shirts tucked into pants. This can make ticks easier to spot and keep them on the outside of clothes. Using a tick repellent on skin and clothing is also highly recommended. The Environmental Protection Agency and Centers for Disease Control list DEET, picaridin, IR3535, oil of lemon eucalyptus, and 2-undecanone as effective active ingredients in tick repellents. Wearing permethrin treated clothing is also particularly effective. If treating clothing yourself, be sure to follow all label instructions and allow the product to dry completely before wearing.

If an attached tick is found, remove it using thin tipped tweezers or forceps. Grasp the tick as close to the skin as possible, and pull the tick upward with steady even pressure. The idea is to remove the tick with its

mouthparts intact to reduce the risk of infection. Other methods of tick removal (i.e., petroleum jelly, heat from matches) are not recommended. Removed ticks can be stored in rubbing alcohol in case disease symptoms develop and the tick needs to be identified. National laboratories can also provide Lyme and other tick-borne disease testing on removed ticks (fees usually range between $50-$100).

Landscape Management

Desiccation (drying out) is a major cause of natural tick mortality. Taking steps to reduce surface humidity and moisture can make an area less favorable for ticks. For example, keeping grass and weeds mowed, clearing leaf litter, and pruning/removing trees to increase sunlight in areas frequently used by people can help discourage ticks.

There is a positive correlation between the abundance and distribution of the blacklegged tick and the size of white-tailed deer populations. Adult blacklegged ticks preferentially feed on deer. Therefore, deer may bring engorged adult female ticks into a landscape where they can lay eggs and increase tick numbers. Deer management options such as fencing, repellents, guard animals, and deer resistant landscape plantings can help reduce tick populations in an area.

Chemical Controls

If landscape management practices fail to provide adequate tick control, insecticides (called “acaricides” when used for ticks) can help reduce populations. Appropriately labeled acaricides should be applied only to areas where ticks may inhabit (e.g., woodland edges, shady perennial beds). It is seldom necessary to treat an entire yard or lawn area because ticks are unlikely to inhabit areas exposed to full sunlight. Common active ingredients used by pest control professionals include those in the pyrethroid class of insecticides (e.g., bifenthrin [Talstar P, Up-Star]; cyfluthrin [Tempo], pyrethrins [ExciteR, Pyganic]). Spray treatments are most effective when applied using a high-pressure sprayer in the early spring. An additional application in the fall can be used to target adult ticks if populations are particularly high. Pyrethroids should not be applied when

pollinators are active, near areas where plants are blooming, or near standing water, streams, or rivers to reduce negative effects to the environment and non-target organisms.

Another option to treat ticks around the home is to target acaracides on small mammals that may be living in the area. In many instances, mice are the reservoir hosts responsible for producing disease carrying ticks (particularly Lyme disease). Rodent targeted devices such as “tick tubes” (e.g., Thermacell), are cardboard tubes containing cotton balls treated with an acaricide. The idea is to spread these around the landscape where mice, or other rodents, will find them and take the cotton as nesting material. Then, any larval or nymphal ticks attached to the animal will contact the acaricide on its fur and die.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed